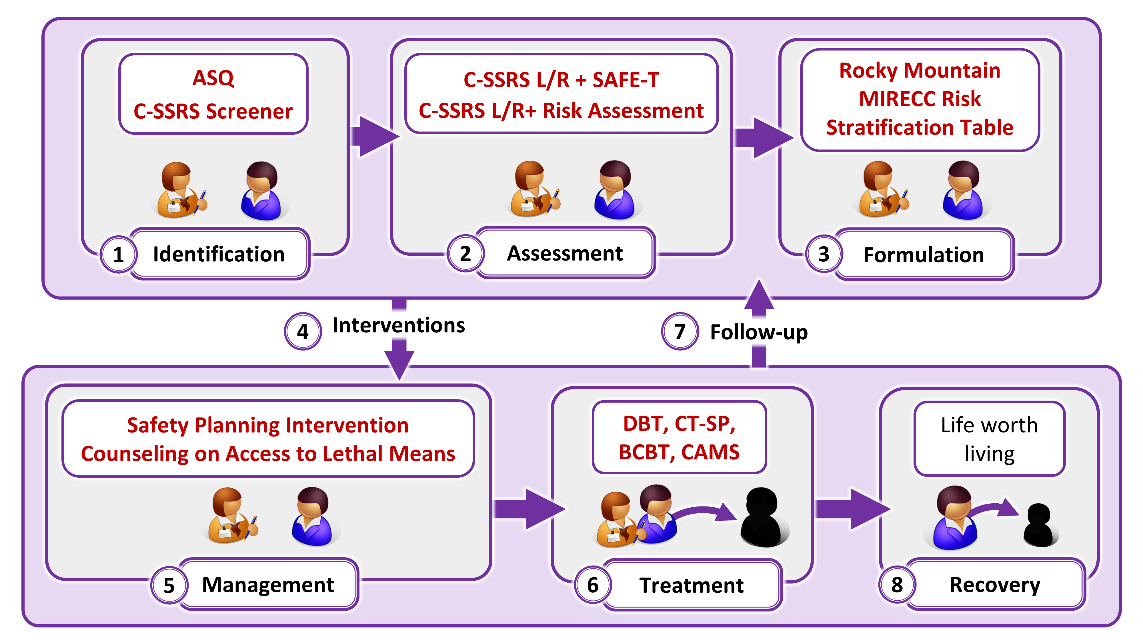

5. Management

We identify four broad categories of interventions to manage suicide risk:

- Addressing behavioral health concerns, including substance use

- Facilitating connectedness

- Safety or crisis response planning for high-risk periods

- Reducing access to lethal means for suicide

These interventions may occur in an inpatient or outpatient setting and are optimally, though not necessarily, collaborative. Some management interventions might not require patient participation at all, such as addressing environmental risks in an inpatient psychiatry setting.

5.1 Addressing Behavioral Health Concerns

Suicide care guidelines differ on approaches to addressing behavioral health concerns, including substance abuse. For example, TJC does not include specific guidelines on psychiatric or substance use disorders, and the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline suggests consideration of ketamine, lithium, or clozapine for specific diagnoses. Recognizing that mental health and substance use disorders are risk factors for suicide, we suggest following standard guidelines for addressing these diagnoses and related problems when these are present.

5.2 Facilitating Connectedness

For individuals identified to be at risk for suicide, TJC identifies a requirement for guidelines for follow-up assessment and monitoring without specifying particular resources for implementing this. Other guidelines focus on strategies for providing or facilitating follow-up behavioral healthcare such as the Zero Suicide Transition element and the VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for Post-Acute Care recommendations for Caring Contacts, Home visits, and the WHO Brief Intervention and Contact.

5.3 Safety or Crisis Response Planning for High-Risk Periods

Among TJC’s resources for safety planning upon discharge from care, we suggest the Safety Planning Intervention (SPI) and the related Patient Safety Plan Template (Stanley-Brown Safety Plan). We also suggest a comparable evidence-based intervention, Crisis Response Planning (Bryan, et al., 2017).

Safety Planning Intervention

Crisis Response Planning

5.4 Reducing Access to Lethal Means

For addressing access to lethal means, TJC recommends the Suicide Prevention Resource Center’s (SPRC) online training, Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM).

Clinicians who are unfamiliar with firearms or cultural factors associated with firearms ownership and use can benefit from training to support culturally-aligned lethal means counseling. A free self-guided course addressing this issue may be found here.